Bone Loss In Shoulder Instability…

Bone Loss In Shoulder Instability…

I have previously written about shoulder instability. At that time, I briefly mentioned that episodes of shoulder instability could cause injuries to the major bones of the shoulder. I want to delve into this topic a little deeper. More recent information shows us that these bone injuries have a critical role in the prognosis and treatment recommendations for those with shoulder instability.

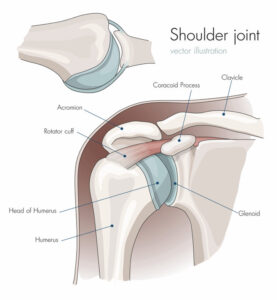

As you may recall, instability of your shoulder is a term that describes when the two bones that form the primary shoulder joint, the Humerus (ball) and Glenoid (socket), become partially or completely separated.

Although this can occur from having “loose” joints, this often results from trauma. Either way, bony injuries to either the ball or socket can result when the ball moves out of the socket. If this happens, bone loss may occur either abruptly or slowly – a little bit with each instability episode over time.

Bone Loss: How Does It Occur?

When trauma forces the ball out of the socket, an obvious fracture or possibly just slight wear of either joint bone may occur. Let’s look at when this happens with the most common type of shoulder instability, anterior instability. Anterior instability is when the ball comes out the front of the shoulder. The same phenomena can occur for posterior instability, as the Humerus is forced out the back of the shoulder. However, the bone injuries would appear on the opposite sides of the injured bones.

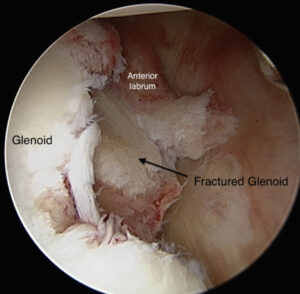

During anterior instability, the ball slips off the front edge of the Glenoid as it goes out the front of the shoulder joint. When this occurs, the back of the ball is likely to contact the front of the socket. If this happens significantly, the bone at the back of the Humerus or front of the Glenoid can fracture.

If a discreet fracture doesn’t occur, wear of the bones may occur, nonetheless. When a fracture occurs, displacement of the fracture fragments can result. Displacement means that the force from the injury moves the broken bone away from the joint surface, essentially lessening the available joint surface.

Alternatively, if simply wear over time, the recurrent episodes can progressively wear down the bone more and more, not unlike sanding down a piece of wood. Either way, the width of the Humerus and the Glenoid can be narrowed as well.

A Bony Bankart lesion is the term that refers to a fracture on the front of the Glenoid. Alternatively, Glenoid bone deficiency refers to less Glenoid bone from any cause – fracture or wear. In contrast, a fracture on the back of the upper Humerus is called a Hill Sachs lesion.

Bone Loss: So What?

As the major bones of the shoulder narrow, instability is more likely to occur and is harder to fix.

Why is instability more likely?

If we think of the Glenoid as a runway on an aircraft carrier and the Humerus as an airplane, we can better understand why narrower bones are problematic. Let’s also assume that the jet will fall off the carrier when its back tires cross the ship or runway’s edge. Therefore when the pilot initiates stopping and hits the brakes, the jet would be more likely to fall off the aircraft carrier if the carrier were shorter rather than longer. Similarly, if the airplane were shorter, the plane’s back tires would be more likely to cross the carrier’s edge sooner, and the plane would consequently be more likely to fall off the carrier, as well. Finally, if both the carrier and the aircraft were shorter, the likelihood of the jet falling off the aircraft carrier would be the greatest.

The bone defects on the Humerus and Glenoid similarly increase the risks of shoulder instability. Even small losses of bone on the Glenoid side, as little as 13% – only a few millimeters – can make a difference.

Why is instability harder to treat when bone loss exists?

Three things provide stability to our shoulders. 1) The muscles around the shoulder, 2) The ligament/labral complex, and 3) The bony anatomy.

Physical therapy will often correct deficits in muscular function. Arthroscopic surgery can routinely fix labral and ligament injuries. On the other hand, bone defects necessitate much more complex procedures, often requiring open incisions, with more extensive tissue dissection, bone grafting, and screws to correct the instability.

Bone Loss: How is it treated?

There are several techniques used to address shoulder instability associated with bone loss. When trying to identify the appropriate treatment, we take into account several individual characteristics. The factors that we consider are:

- Age

- Activity level

- General shoulder looseness, or laxity, of the patient’s joints

- Location of the bone loss (Glenoid, Humerus, both)

- Amount of bone loss

We only consider surgery for shoulder instability if the instability is recurrent or there is a relatively high likelihood of recurrence. Younger people, those involved in more risky (contact sports or forced overhead activities) activities, and those with preexisting shoulder laxity are more likely to have recurrences. As we mentioned above, so are those with greater degrees of bone loss. It appears that those with more of these factors are at an even greater risk of recurrence. As a result, surgery to correct instability in these cases can be more complex. For instance, when bone loss exists, we often must use additional surgical techniques to account for these deficits.

Bone Loss: Available Procedures

Different procedures are appropriate based on the location and the degree of bone loss. First and perhaps most importantly, not all bone loss needs to be addressed. Lesser degrees of bone loss, or bone loss in older and less active individuals, often can be treated as if there is no bone loss. In those cases, an arthroscopic labral repair will usually be adequate. But if there is more significant bone loss or bone loss in association with other risk factors, then additional or completely different procedures will be needed. As a result, in those at a greater risk for recurrent instability, even with no consequential bone loss, surgery will often be recommended earlier to avoid developing significant bone loss.

But when significant bone loss does exist, there are surgical procedures available to correct it….

Humeral Bone Loss

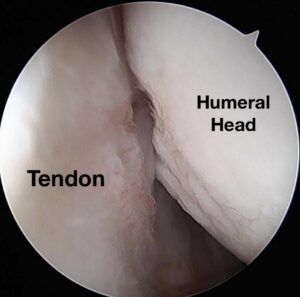

When indicated, we can perform an additional arthroscopic technique called a Remplissage procedure during the same surgery as your arthroscopic labral repair.

The Remplissage procedure involves attaching one of your rotator cuff tendons to the area of bone loss in the back of your shoulder (Hill Sachs Lesion). This attachment acts as a check-rein that restricts your Humerus from moving too far forward.

If we go back to the jet and aircraft analogy, the Remplissage functions much like the arresting cable that gets snagged by the jet’s tailhook at the back of the plane. These wires prevent the aircraft from traveling too far forward and thus help to prevent the airplane from falling off the carrier. The Remplissage works in the very same way for your Humerus and prevents it from falling off your Glenoid.

Alternatively and rarely, your surgeon can fill the bone defect in the back of your shoulder with a bone graft covered by cartilage and obtained from a cadaver. Depending on the size of the needed graft, this may be performed arthroscopically. However, usually, this procedure is completed through a larger open incision.

Glenoid Bone Loss

When our Glenoid is short, or, as in our example, the aircraft carrier is short, our runway is short, and our Humerus, like a landing aircraft, is more likely to fall off the front. However, if we lengthen the runway, this becomes much more difficult. So when we have Glenoid bone loss, we aim to extend the Glenoid from front to back using a bone graft.

There are several ways to achieve this, all with some advantages and disadvantages. But overall, the success rates of these procedures are similar and overall very good. First, some techniques use your bone – autograft, and some use the bone of others who are deceased – allograft.

Autografts…

Autograft options include using your coracoid (see picture above), a small bone in the front of your shoulder, along with its attached tendons – moving this from its native location and fixing it to the front of your shoulder. This procedure is called a Laterjet or Bristow procedure. Alternatively, bone from the crest of your pelvis can be harvested and fixed to the front of your Glenoid.

Allografts…

The allograft options can also include bone from the pelvis crest, but a more enticing prospect is using a distal tibial allograft.

It turns out that the curve of all of our joint surfaces is the same, no matter the joint. As a result, using bone from the more readily available distal tibia (end of our leg bone at our ankle) is possible. This graft not only matches the natural curve of our Glenoid, but it allows for a larger, more dense graft coated on the joint surface by cartilage, just like our native Glenoid. These are benefits that other grafts, including the autograft options, cannot match.

It appears that the denser, more significant bone enables a better fit to the Glenoid with a graft that is less likely to absorb over time. Additionally, the more normal joint shape and cartilage covering the graft will hopefully result in lesser degrees of degenerative joint changes over time.

Most surgeons perform these procedures through an open incision. Some centers have shown promising early results when performing similar operations arthroscopically.

Take-Home Lessons

Bone loss associated with instability can result from greater instability forces or numerous less violent instability episodes. This bone loss can occur on both the Humerus and Glenoid. Even lesser degrees of bone loss can lead to more frequent shoulder instability. Such bone deficiency can require more complicated surgical procedures to correct your instability. Often, these surgeries necessitate either a tendon transfer or an open bone graft.